Why Extreme E's equality stance is necessary

The rules of the new electric SUV off-road series require teams to field one male and one female driver. The move is an easy one to criticise, but the reasoning behind it is clear when the challenges still facing female drivers are explained, says JAMES NEWBOLD

During the online launch for the new all-electric SUV off-road Extreme E series, which mandates a fifty-fifty split between male and female participants, Chip Ganassi Racing’s long-serving general manager Mike Hull was asked a pertinent question. What was the response to his team hiring a female driver, Sara Price, for the first time in its storied 30-year history?

“Sara has proven that she can win and that has nothing to do with gender,” Hull replied. “She knows how to win and she’ll represent Extreme E and the global significance of what we’re trying to do as a winning race driver, who happens to be female.”

The brainchild of Alejandro Agag, XE is the latest avenue to offer female drivers a platform to showcase their skills. Unlike W Series, however, they will be pitched head-to-head against their male counterparts, and in equal equipment.

While high-profile drivers such as Sebastien Loeb (X44), Carlos Sainz Sr (Acciona) and Mattias Ekstrom (Abt) have tended to hog the headlines, the likes of Price, Molly Taylor (Rosberg Xtreme Racing) and Catie Munnings (Andretti United) will have an invaluable opportunity to demonstrate their talents to audiences who may never have heard of them, and to become stars of the series in the way unheralded Formula 1 refugees such as Sebastien Buemi and Lucas di Grassi became the standard-bearers in Formula E.

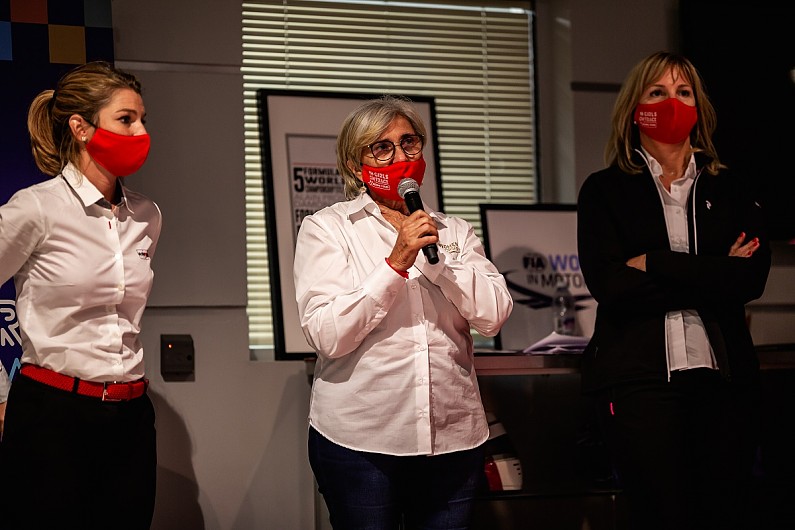

Unsurprisingly, the “revolutionary” sporting format, which requires both the male and female driver to complete one lap in each heat, has the full support of FIA Women in Motorsport Commission president Michele Mouton.

“For many years we have been striving towards gender equality and equal opportunities in the sport,” she said at the launch. “Extreme E is supporting this philosophy and has taken a concrete action that highlights female racers’ competence, and it’s for me a very important element. We are really supporting seeing more women competing in a mixed environment and we are extremely pleased with this great opportunity for them.”

There can be no doubt that XE’s stance points to an encouraging shift in the opportunities being provided to female participants in motorsport, but there will always be critics who deride it as a case of artificial positive discrimination. Surely, according to their logic, if a woman was good enough to be selected on merit then a team would do so without being forced to.

But the reason for Extreme E taking this bold stance for equality is a simple one: lack of funding and visibility of female drivers is creating a vicious circle that means the talent pool is far smaller. This will take time to resolve but, as Agag reasons, “it’s a task that’s worth it”.

The problem

In three of the four years between 2010 and 2013, there were four female drivers on the starting grid for the Indianapolis 500. But in 2020 there were none, for the first time in two decades. The impact of COVID-19 certainly played its part in Pippa Mann being unable to continue her run of seven consecutive appearances at America’s biggest race, but hardly explains why the Indianapolis-based Brit was the only one in a position to continue the streak started by Lyn St James in 2000.

“We’re effectively pitching still to a mostly male audience who’s controlling the money. And with all human beings, let’s be honest, it’s much easier to relate to someone who is more like you” Pippa Mann

Mann has become a specialist in one-off deals at the 500 since graduating from Indy Lights in 2011, and found most success with sponsors based near to the Speedway, having discovered larger companies to be a closed door unless “they have a vested interest in potentially supporting women, which narrows my field significantly”.

It shows that things have changed little since the start of St James’s own Indy foray – the long-time IMSA racer famously had 150 sponsorship proposals rejected over a four-year spell before snaring JC Penney and becoming rookie of the year in 1992.

“The biggest hurdle still in my opinion for any racing driver, whether male or female, is the sponsorship side and literally being able to find the money to keep competing,” says Mann, who recently announced that she will contest the 2021 Nurburgring 24 Hours as part of the Girls Only Audi GT4 team that, as well as drivers, is staffed by an all-female crew of mechanics and engineers.

“But for women in motorsports specifically, that presents additional hurdles, because we’re effectively pitching still to a mostly male audience who’s controlling the money. And with all human beings, let’s be honest, it’s much easier to relate to someone who is more like you.

“Plus, you still have the lingering stereotypes that may not be directly affecting the person who is making the decision, but the person deciding whether to award this sponsorship money and who is going to get it has to do so based on what’s best for their brand. And there’s still that small but relatively vocal portion of the population who certainly make themselves heard when female race car drivers are involved. It’s different if I am involved in a crash, whether it’s my fault or not, than if a male driver is 90% of the time. That’s just a fact.”

“It’s no secret that motorsport is really expensive,” agrees Formula 3 racer Sophia Floersch, who broke into sportscars last year with the all-female Richard Mille Racing LMP2 team. “If your parents don’t have the money every single year to pay €1-2million, or partners or sponsors or people like Richard Mille believing in your story, that’s where it gets more difficult for women because there is never a really performing woman in top motorsport ranks where sponsors see that women are actually able to do it.

“So sponsors are like, ‘Yeah, but first you have to prove it’, and you don’t just have to prove it once, you have to prove it five times that you’re actually as quick as the men. And it’s like a circle, because you are not able to win a race if you don’t have the same test days as the others. Even if you have testing bans in F3 or F2 or whatever, people can still find a way to go around those things. So I think that’s the biggest issue, that women are not getting the same sponsorship deals.”

Sportscar stalwart Katherine Legge says that she’s “been around long enough and bullied enough people into believing me” that she can match her male counterparts, but struggled all the way through her Champ Car, DTM and Indycar careers to open doors with teams that could give her a chance of winning. And that, she agrees, is part of the problem.

“We would all get opportunities, but it wouldn’t be with the Ganassis and the Penskes of this world,” she says of her time with PKV, Dale Coyne Racing and Dragon in Indycars.

Mann, a member of US-based female collective Shift Up Now, which aims to help more women get opportunities in motorsport, says it’s a constant point of frustration that the lack of female representation in Formula 1 is often couched in terms of ability – “When is there going to be a girl good enough to be in F1?” – when then-IndyCar rising star Simona de Silvestro’s time as a Sauber-affiliated driver never amounted to an opportunity to test contemporary equipment.

F1’s door remained firmly closed to the Swiss, who Mann acknowledges is “possibly the best female driver in a high-level open-wheel car that most of us have ever seen on a road course” (and who is now Porsche’s FE reserve). With the problem of sponsorship persisting, Mann says it’s no surprise that progress is slow.

“When women are funded enough the entire way up the ladder to gain the same experience in the same level of teams as their male counterparts, that’s when you’re going to start to see women be ready for Formula 1,” Mann says.

“We can be as quick as the top of the guys, I’m 100 per cent sure that a woman can do the same,” agrees Floersch. “But we still need to get the same testing days, the same new tyres, the same chances.”

The way forward

So what’s the answer? “It’s really got to be a numbers game,” says Legge, a member of Mouton’s Women in Motorsport Commission since it was founded. “You get more girls involved at grassroots level when they’re young, and more of those will then make their way up through the ranks.”

Mouton is, of course, all too aware of this and is actively working to address that very point.

“When I first started it was more of a novelty and now it’s not really a novelty anymore. More and more girls are proving that we can be competitive, so it’s not an anomaly” Katherine Legge

“We have a pyramid and what is missing for us is the base of our pyramid,” she says.

More than 1200 girls aged between 13 and 18 entered the FIA’s Girls on Track Karting Challenge, a national selection held in nine European countries in 2019 for aspiring racers with or without experience, from which six with the most potential were picked out after a final assessment at Le Mans.

The Commission has also partnered with Ferrari on the Girls on Track Rising Stars programme, a driver selection held at Paul Ricard to discover a new member of the Ferrari Driver Academy to race in Formula 4, although that was postponed in November due to a positive COVID test for one of the final four drivers. Nevertheless, Mouton was pleased by what she saw and encouraged for the future.

“We have seen now in Le Castellet, we had very good potential, girls who were very good and adapting very quickly on Formula 4,” she says. “They will be our resources for the future so I am quite convinced that we are on the right way.”

That optimism is shared by Legge, who notes “opportunities now for women in racing are thousands of times more than when I first started”, with W Series offering a platform for young female drivers to race for free on the support bill of eight F1 weekends in 2021.

“I wish I was 20 years younger honestly!” she says. “Back when I moved to the States [in 2005], there was literally Danica [Patrick], myself and Susie [Wolff], so three of us racing globally professionally, and now there’s a lot more. When I first started it was more of a novelty and now it’s not really a novelty anymore. More and more girls are proving that we can be competitive, so it’s not an anomaly.

“Times are changing. Doors are opening, which is going to make the nine-year-old Katherines of the future have more opportunities, and it’s really cool to see that unfold during my career. I think it’s going to explode here in the next 10 years or so and I think we’ll see females in F1 and all the top ranks of racing.”

And as more female drivers prove themselves at the top, Mouton believes that more young karters will be encouraged not to give up on their dreams in an altogether more positive cycle. When the right female driver gets the right opportunity, Mouton believes “there is no reason” why she would not be able to take it.

“I tell you, it was happening for me,” she says. “When I was in the French Championship, I was lucky enough to have a manufacturer who gave me the same car, the Fiat, as the best driver in France and for me to have the same condition. I didn’t want to be ridiculous compared to this guy – I had to push.

“Then Audi called me for the world championship against the best drivers in the world and then you have the same car, they treat you the same way, same testing and you think you will be three seconds slower per kilometre? No way! It pushed my limit.”

Whether or not XE will prove the catalyst for meaningful change is impossible to say for now. But there is rightful optimism that XE’s equality stand can be a focal point to inspire young girls to have a go themselves and, ultimately, for female participation to continue its upward trajectory to a point where many more are pushing to upend a status quo that required a fifty-fifty rule to be introduced in the first place.

Transformative change may not happen overnight but, as Mann points out, “change is happening all around us”. That, surely, can only be a good thing.